Creative technologist Adrian Jones started a new project with a vision: to reflect Pittsburgh’s past with its present, revealing stories and wisdom for a better future.

Creative technologist Adrian Jones started a new project with a meaningful vision: to compare Pittsburgh’s past with its present, uncovering stories and wisdom that enable a better future.

His plan was to do everything directly from our smartphones.

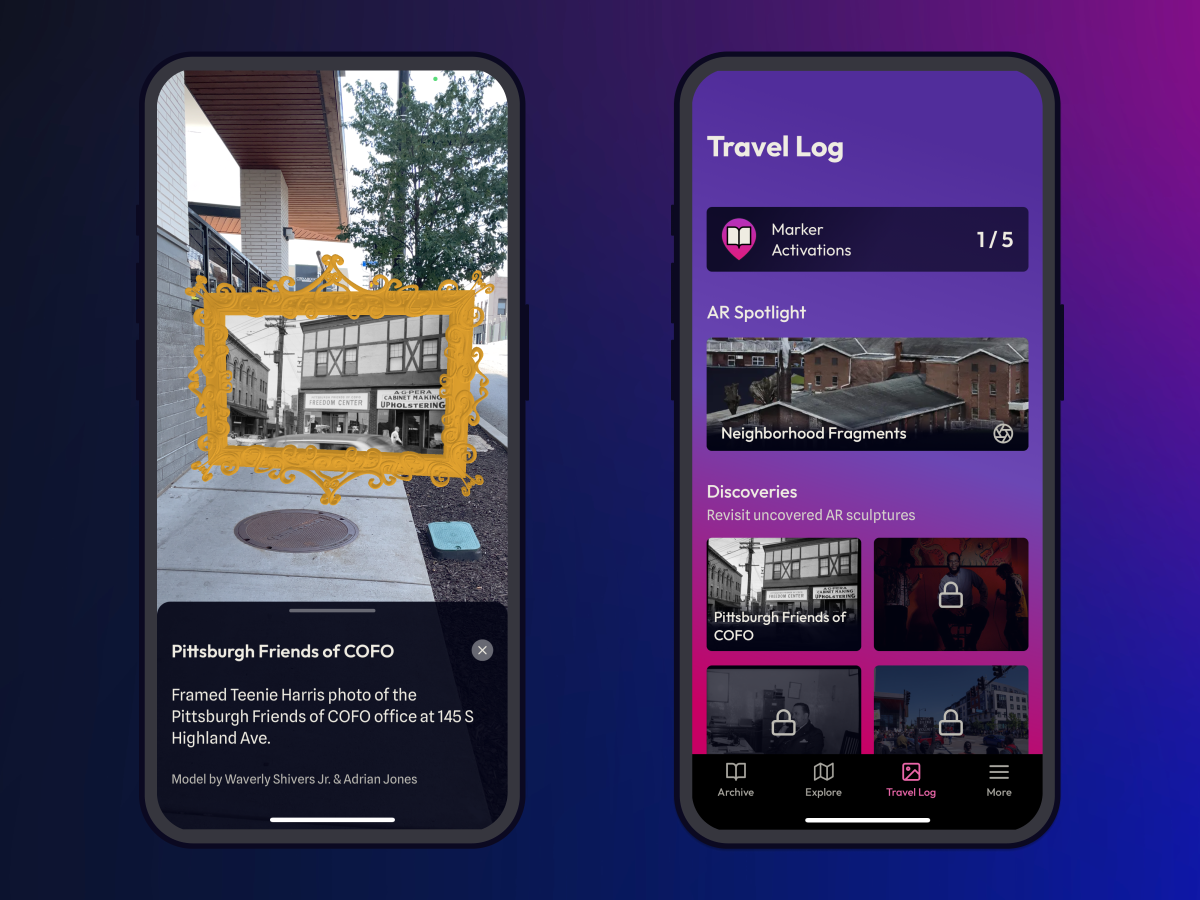

Jones brought that vision to life by founding Looking Glass, an interactive app-based archive that uncovers hidden stories of Black life in Pittsburgh.

Launched in June, the app combines augmented reality (AR) with historical archives to connect the past, present and imagined future. Users can travel through Pittsburgh and discover memories that have shaped the city’s neighborhoods. Currently, the app is primarily highlighting the rich history of East Liberty.

“It was important to me that we start with East Liberty because that’s where a neighborhood is being radically transformed and so many people are being displaced,” Jones said.

According to East Liberty Development, Inc., the neighborhood was home to a vibrant commercial district and a close-knit residential community in the 1940s and 1950s. It declined rapidly in the 1960s after an urban renewal program sought to transform East Liberty into a neighborhood that could compete with new suburban markets.

While well-intentioned, this initiative resulted in a deconstruction of East Liberty that left it largely unrecognizable and inaccessible, causing disruption and displacement of residents. The new AR app shows how some notable sites developed alongside the neighborhood.

Looking Glass’s main feature is the Explore View, where users navigate a map marked with markers of significant people, events, and institutions. Explorers can activate site-specific AR sculptures and view artifacts such as photos and videos.

“I was wondering: What if you could unearth buried history?” Jones said. “AR is one of the things that offers these kinds of creative opportunities.”

Documenting gentrification through art and technology

Jones’ path to founding Looking Glass began when he moved from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh in 2017.

After scouring Pittsburgh’s archives, hearing stories from the community, and reflecting on his own experiences, he became interested in the cycle of disinvestment and displacement – or erasure through gentrification.

His interest evolved into an idea while attending the first class of Collective Action School, an experimental online school for tech workers that combines activism, design, and software development. That year’s theme of “Creative Protest” inspired Jones to create what eventually became Looking Glass.

“I understood creative protest as a call to take stock of my skills and the problems in my immediate environment so that I could find a place where I could strategically intervene and serve my community,” Jones said. “I had this vision of a lens that could reveal the history and stories that are blatantly hidden, especially in gentrified neighborhoods.”

The project was overseen by advisors Xiaowei Wang, Ph.D., and Dorothy R. Santos, Ph.D., both accomplished writers, artists, and scholars who serve as administrators of the Collective Action School.

“I think this project is a celebration of Black joy, Black lives, Black history and also Black futures in Pittsburgh,” Wang said. “Places like Pittsburgh have such a rich history of resistance and community.”

Wang and Santos, along with two others, founded the Collective Action School – originally called the Logic School – in response to growing calls for change in the tech industry. They envisioned a program that offered a critical, interdisciplinary approach to technology. The school was created to equip tech workers with the tools and knowledge to transform the industry from the ground up, with a focus on community building and issues of equity in technology.

An independent technology partner with diverse support

Notably, Jones built the technical infrastructure for Looking Glass himself, eliminating the usual limitations of app development, such as expensive licensing fees, data collection, and user monitoring.

By developing the app in-house, better protection was ensured and Jones was able to fully design the user experience.

“I think it’s important that there are more examples of technology that is developed and designed exclusively by people of color,” Jones said. “It’s important and a differentiator that (Looking Glass) was self-developed and can be owned by the community of contributors and was created entirely by black and brown hands.”

Jones also engaged a diverse group of BIPOC contributors in the creation of Looking Glass and its accompanying features, covering mediums such as soundscape, videography and brand design.

Pittsburgh-born singer-songwriter, musician, producer and sound engineer Danielle Walker, known as INEZ, produced original music for the app. She said her songs reflect the unrest of East Liberty residents reclaiming their identity and fighting back against gentrification.

Walker said storing those records on a mobile device and viewing landmarks through an AR lens will ensure that “fewer things are erased – that the families who were in East Liberty and knew its heart can keep a piece of it, even as it changes.”

A spotlight on black history and the power of collective action

The beta version of the app was launched on June 29 at Emerald City in downtown Pittsburgh, where staff and supporters came together to celebrate the app and explore other interactive story stations.

One room featured three virtual reality (VR) stations that immersed guests in the world of black art, history and memory. Another room featured a short film directed by Jones called “A Walk to Enterprise & Frankstown,” which gave viewers a walk from the audience’s perspective to the site where Local 471, Pittsburgh’s former union of black musicians, once stood.

The app is currently available for download on iOS and will soon be available on Android. New features are being added continuously and the beta version for Android is expected in August.

In the future, Jones plans to incorporate new features into Looking Glass, including an audio library where users can listen to oral histories and original music from local musicians.

“I want the archive to be able to house stories from all over the city. East Liberty is just the beginning,” Jones said. “There are stories everywhere, right under our feet.”

In addition, Jones hopes that Looking Glass will serve as a blueprint for similar projects in other cities.

“I hope this tool will give people at large easier access to Black stories and visions of Black futures,” Jones said. “It’s about opening up pathways to healing and collective action.”