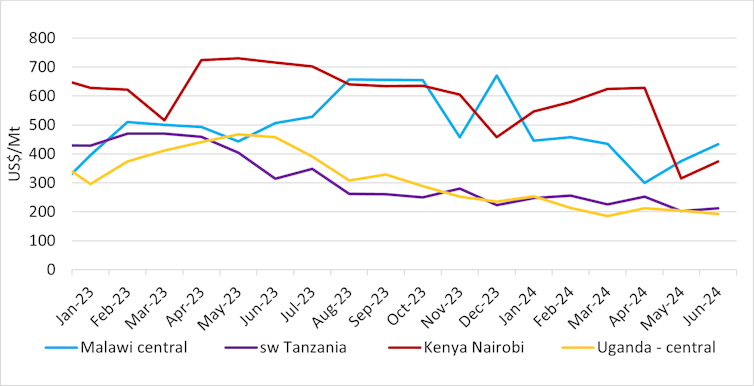

For more than a year, maize prices in Kenya and Malawi have been significantly higher than in other countries in the East and Southern Africa (ESA) region.

This can be explained by several factors.

In Malawi, high fertilizer prices and the resulting reduction in fertilizer use had a negative impact on maize supplies. Bad weather and trade bans exacerbated the situation, leading to lower than usual production.

In Kenya, high maize prices have been driven up by excessive margins. Sellers are charging prices above the import parity price – the price of maize from surplus-producing countries plus the transport costs of importing it into Kenya.

This is particularly worrying for a country where some 1.2 million people are suffering from acute food shortages.

We are economists at the African Market Observatory, which monitors staple food prices and researches market dynamics, including market concentration and barriers to entry, within and across ESA countries. The analysis is complemented by in-depth fieldwork.

Maize grain prices in selected countries in East and Southern Africa (Fig. 1)

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from partners of the African Market Observatory (AMO)

Maize is the most important staple crop in the region and is often traded across borders to meet overall regional demand. Tanzania is the leading producer of non-GMO maize and exports it to other countries in the region. Since 2023, Tanzania has been a major source of maize exports to the region, achieving record harvests thanks to above-average rainfall.

Malawi generally produces enough to meet its needs, while Kenya is always a net importer of maize due to its large population.

If maize markets functioned well, prices in Kenya and Malawi would consistently reflect prevailing prices in surplus-producing countries in the region, such as Tanzania, in 2023 and 2024. Competition authorities should take a regional approach to ensure that markets function well in terms of pricing and trade.

This includes monitoring markets, assessing barriers to regional trade and intervening in cases of anti-competitive behaviour.

Malawi’s poor harvest

Normally, Malawi can exceed its annual maize demand of around 3.1 million tonnes. However, in 2023, the country recorded a poor harvest. This is attributed to low fertilizer stocks and low use in 2022.

Fertilizer use increases the amount of crop grown per area of land (yield). In May 2022, Malawi experienced a significant increase in fertilizer prices (such as urea) due to supply shocks that pushed up prices globally. World prices subsequently declined while fertilizer prices in Malawi remained high, and in general, fertilizer prices in the country were higher than in its neighboring countries. Compared with five other countries in the region (including Zambia and Kenya), Malawi had the highest fertilizer prices and markups.

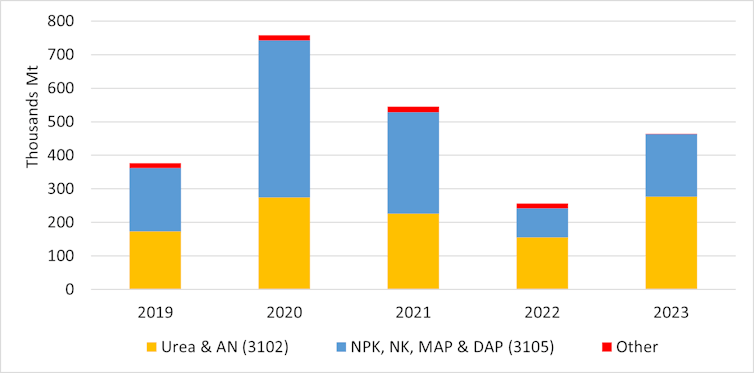

Given the high prices, farmers bought less fertilizer. Fertilizer imports in 2022 were about half of the volume in 2021 (Figure 2).

Delays in the procurement of fertilizers through Malawi’s Affordable Input Programme further exacerbated the problem. The government programme normally provides 250,000 tonnes of fertilizer to 2.5 million households on a subsidised basis.

Some parts of Malawi were hit by Cyclone Freddy in March 2023. However, only 440,000 acres (178,061 hectares) of arable land were affected. According to our estimates, this was about 10% of the total cultivated area.

This means that the poor harvest in 2023 is largely due to low fertilizer use.

Malawi’s fertilizer imports by year (Fig. 2)

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from ITC TradeMap

Tanzania, on the other hand, has had a good harvest, producing an estimated four million tonnes of maize surplus this year. That is seven times Malawi’s forecast import needs for 2024 and enough to cover the region’s overall deficit.

If regional markets were functioning as intended, the price of maize in Malawi would be equal to the price (plus associated import costs) at which maize would be purchased in Tanzania. We estimate that the import parity price at June 2024 prices was US$265 per tonne. Maize was sold in Malawi for US$433 per tonne, a difference of US$168, or a premium or “excess margin” of 63%.

The price of maize in Malawi is much higher than it would have been if there had been normal trade between the two countries.

Dynamics of Kenyan maize cultivation

Kenya’s maize production averaged nearly 3.4 million tonnes per year between 2020 and 2022. To meet its annual consumption of 4 million tonnes, the country was a net importer of maize.

Kenya imports maize from Tanzania and other countries in the region, including Uganda and Zambia. In 2023, about 43% (219,260 tonnes) (ITC Trademap) of Kenya’s total maize imports came from Tanzania.

Against this background, Kenya’s maize prices should be similar to those of its trading partners – that is, at import parity levels. However, maize prices in Kenya are much higher than in the rest of the region.

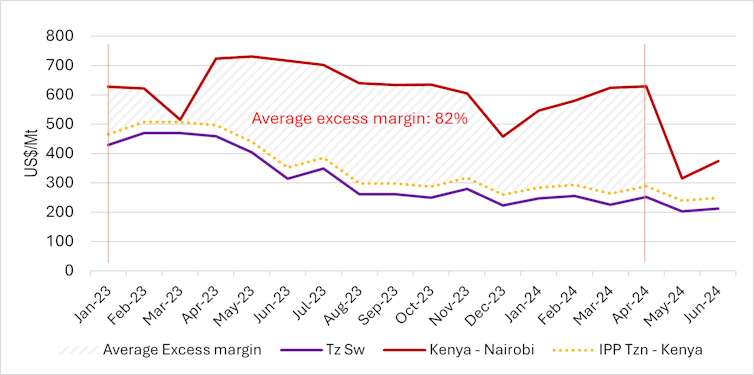

From January 2023 to April 2024 (Figure 3), prices in Kenya were raised well above the cost of importing maize from southwest Tanzania, the maize-producing region. During the same period, the average price in Kenya was US$624 per tonne. We calculate the average import parity price to be US$359, resulting in average excess margins of about 82% between January 2023 and April 2024.

Kenya’s maize prices (Fig. 3)

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from AMO partners

Most recently, the price of maize in Kenya almost halved from over US$600 per tonne in April 2024 to US$315 in May 2024, before rising to US$374 in June 2024.

This maize price is still above the import parity price from Tanzania of around US$249, meaning there is a 50% overspread on the maize price in Kenya. Overall, maize prices in Tanzania have been declining since the April 2023 harvest due to record production in 2023 and 2024.

The sharp decline in maize prices in Kenya is likely due to imports from neighbouring countries (such as Tanzania and Uganda) and the entry into the market of maize that producers had hoarded in the hope of being able to sell it at higher prices.

This underlines once again that maize markets in Kenya are not functioning well because producers have the ability to distort prices by restricting supply.

Dysfunctional regional markets allow traders and producers to continue to charge higher prices for maize in Kenya. In well-functioning regional markets, cheaper maize from neighboring countries would drive down maize prices in Kenya.

Corn markets in Malawi and Kenya are not functioning

The markets in Kenya and Malawi are characterised by excessive margins and high prices for maize and key raw materials for maize production. This is further exacerbated by the fact that the regional markets do not function well in terms of pricing and trade.

This requires competition authorities to take a regional approach in monitoring markets, assessing regional barriers to trade and intervening in cases of anti-competitive behaviour.