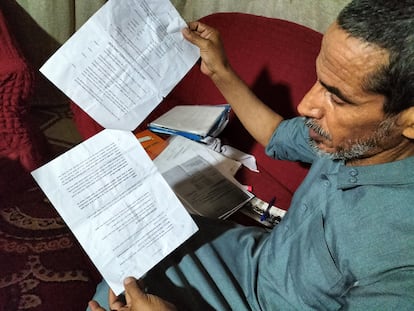

Riad El Shtiwi opens a folder of documents in Arabic and Hebrew that he has amassed over decades to explain how he got here while his wife, Widad, and four of their children (who were born in Israel) are in Gaza, facing hunger and bombings. “Here” is hard to define: a precarious town in Israel’s Negev desert that has no official name and is not on any maps, like dozens of other so-called “unrecognized settlements,” most of them Bedouin. It is known as Tel Arad because of its proximity to an archaeological site of the same name, which lies about 25 kilometers from the Dead Sea, though the two are separated by an unmarked dirt road ridden by camels that were the family’s mode of transport on their journey through three different territories (Egypt, Gaza and Israel) — a metaphor for half a century of conflict in the Middle East.

In 2005, Israeli authorities relocated El Shtiwi and 68 other families from the Armilat – a Bedouin clan originally from the northern coast of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula – to Tel Arad, expelling them from a place that had a name (Dahaniya) but is known in Gaza by another nickname: the “village of traitors”.

It was built in the 1970s by the Israeli military authorities (when they controlled both Gaza and Sinai after their victory in the 1967 Six-Day War) to compensate them for appropriating their land to build the Jewish settlement of Yamit, and for siding with and spying for the Israelis during the conflict. When Israel and Egypt signed a peace treaty in 1987, part of the clan returned to Sinai. Riad’s family moved to Dahaniya, where there was running water, electricity, and half a hectare of land per person.

When the Oslo Accords between Israelis and Palestinians came into force in 1994, Gaza (along with Jericho in the West Bank) became the first place where the Palestinian flag flew, and Dahaniya became a place guarded by separation walls and Israeli soldiers. Residents carried weapons at night, and a distinctive gap separated the Bedouins from the Palestinian collaborators Israel had deported to this place during the First Intifada (1987-1993) so that they would not be murdered in the West Bank for passing on information to the enemy. Israelis and Palestinians agreed to keep Dahaniya under Israeli sovereignty “until a general (Palestinian) amnesty is declared for the residents of the village.” Such a declaration never came, nor were they ever freed from their stigma.

Then, in 2005, Ariel Sharon’s government unilaterally decided to withdraw its troops and 9,000 settlers from Gaza, which had become a flashpoint in the conflict, and instead focused on the West Bank. Images from that time have gone down in history: those of soldiers violently evicting Jewish settlers dressed in orange, the color of the anti-disengagement movement. At the time, no one cared much about the fate of the “village of traitors.”

Although Israel built Dahaniya, it was not included in the evacuation compensation plan, so its residents received less money than the Jewish settlers. Staying in the new Gaza, with the stigma of collaborators hanging over their heads and without the protection of Israeli soldiers, was a risky option. Some returned to their native Egypt, others petitioned the Supreme Court for extradition to Israel. The case landed on Sharon’s desk, who decided to grant them temporary residency until “it becomes clear” whether their lives would really be in danger in Gaza.

The military left them near inhospitable Tel Arad, with tents and a tanker truck for water. In stories from the time, the evacuated members of the clan complained of this new life, lacking fertile land on which to grow their tomatoes and not even electricity. Not to mention that the truck leaked, so they had to drive miles to get water. “They took us back 30 years,” El Shtiwi recalls as the women prepare the lamb and rice they will eat for dinner sitting on the ground next to the fire.

For the Bedouin families already living in the zone, the tanker was a slap in the face after years of unsuccessfully pleading with the Israeli authorities for a connection to the water and electricity network. The nearby Jewish communities were also unhappy with the arrival of a “weak and unemployed population” that “will only increase the crime rate in the area,” as the mayor of the city of Arad, Moti Brill, said at the time. A week later, after sermons were held in local mosques against the new arrivals, the Bedouins in the area opened fire on their homes. They fled and returned to the Gaza border, but the military authorities remained firm: it was Tel Arad or nothing. “They forced us to come back,” complains Shtiwi.

“Now I am happy to be in Israel, I have no regrets. I did not want to stay in Gaza or leave (to Egypt). But I am also surprised that they took us to a place where there is nothing, a mile from the main road,” he continues.

Antonio Pita

The authorities do not recognize Tel Arad or other nearby settlements (some of which were founded before the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948) in order to pressure residents to move to the cities and abandon their traditional way of life. Their goal: to free up the area for the expansion of Jewish towns and military training bases. Since their communities are not legal, building is not legal either. “All of this is facing demolition orders,” says El Shtiwi, pointing to two buildings. This dynamic is in stark contrast to the Jewish settlements in the West Bank, which the State of Israel considers illegal: it is quite unusual for them to be demolished, and over time they receive protection, money, war, access roads and public infrastructure.

Today, the Gaza side of the Kerem Shalom border terminal with Israel stands on the former site of Dahaniya. It was once part of the airport that was briefly located in Gaza, a dramatic symbol of the shattered dreams of the peace process. Built with international funds, the airport celebrated its first flight with much pomp and circumstance in 1998. Four years later, in the midst of the Second Intifada, Israel bombed its radar station and control tower and bulldozed the runway.

Today, El Shtiwi, 47, is anxious to get Widad, whom he calls his second wife, out of Gaza even though they have no legal status due to Israel’s 1977 ban on polygamy. Widad, 44, is from Rafah. They married in 2007 and had three children (now aged 15, 14 and 11) during a period when El Shtiwi lived in Gaza. In 2016, when he was in Israel, she entered on a medical visit permit and took the opportunity to stay in Tel Arad.

“We built a house and the children went to the local school,” Shtiwi recalls. They had four more children (now aged between three and seven), who were born in an Israeli hospital called Soroka and were educated in the country. Two years ago, they were deported to Gaza because of their illegal migration status.

The authorities do not like polygamy, which is practiced by a third of the Negev Bedouins but is not legal. Shtiwi had to take a DNA test to prove that he is the father of the children and to demand their return. He received the results of the test on October 2, 2023.

Five days later, Hamas launched its brutal surprise attack, Israel began ravaging Gaza, and everything (getting someone out of Gaza, dealing with the paperwork) became a herculean task, although now it was even more urgent. After petitions and appointments with the Interior Ministry, El Shtiwi submitted his family registration form on July 29 and says he will receive a response in six months. “Do you realise what it’s like to spend six months in Gaza now?” he asks. “Sometimes I think, ‘It’s war, it’s complicated.’ But then I realise it’s the other way around. It would take 10 minutes: someone takes them to Kerem Shalom and gets them out that way. Hamas will not object,” he says.

Meanwhile, Widad spends her days with her children and lives on welfare in a precarious tent near the town of Khan Yunis, having fled advancing troops to Rafah, where they lived in four concrete walls. “In Rafah, we were not happy because we wanted to return to our home in Israel and the children wanted to be with their father. Now we are even worse off, in a tent where it is very hot. People ask me: ‘Your husband is an Israeli citizen, why doesn’t he receive you and your children?'” she says via voice and text message on WhatsApp. “Life is really hard.”

Register for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition