Getty Images

Getty ImagesHurricanes are classified by wind speed, ignoring the cause of 90% of deaths in extreme storms. Scientists are working hard to update the imperfect system we rely on to warn how deadly a storm will be.

The damage caused by Hurricane Ernesto is devastating in Puerto RicoThe storm received the lowest rating on the official hurricane categorization scale, the Saffir-Simpson scale, due to its 75 mph wind speed. But storms that are just at the lower end of the hurricane scale can cause just as much damage as a Category 5 hurricane. (Read more about Why we underestimate Category 1 hurricanes.)

As climate change brings stronger storms and more extreme hurricane seasons, calls are growing to rethink how hurricanes are rated. While the Saffir-Simpson scale is widely known and has been used for over 50 years, it has significant flaws that make scientists question whether it is the best measure for the job.

There are several new approaches aimed at improving the Saffir-Simpson scale and ultimately helping to save lives through better warning systems.

The water problem

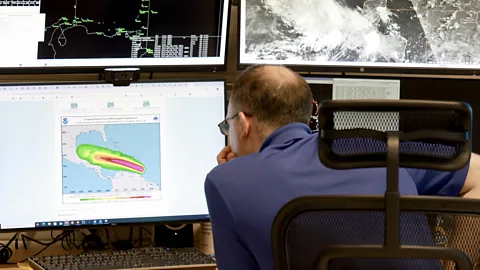

The scale was developed in the early 1970s by Herbert Saffir, an American civil engineer, and Robert Simpson, a meteorologist. It measures the maximum sustained wind speed of a storm. On this scale, hurricanes are rated on a scale of one to five, with five being the most intense. The wind speed is measured by reconnaissance aircraft They are flown by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and drop instruments that measure pressure, wind direction and speed as they fall toward the sea.

Getty Images

Getty Images“The Saffir-Simpson scale is inadequate,” says Michael Wehner, a senior scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California who specializes in the changing behavior of extreme weather events. “The problem is that the scale only measures the highest wind speed at any point in the storm. But most of the damage is caused by water, not wind.”

“The maximum wind speed has very little to do with the storm surge,” says Vasu Misra, a professor of meteorology at Florida State University’s Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies. “The storm surge is proportional to the wind tension,” he says. Tension is the force that the winds exert on the ocean surface, he explains.

“So it’s more about the horizontal distribution of winds around the tropical cyclone than a point estimate,” he says.

Storm size

The Saffir-Simpson scale does not take into account the overall size of a hurricane or the horizontal distribution of winds, he adds.

Misra has proposed a new metric to measure the destructive power of hurricanes to complement the Saffir-Simpson scale. Known as Tracking integrated kinetic energyor Tike, the metric measures the size of the wind field as well as the intensity and duration of the storm. Instead of using reconnaissance aircraft, this method would rely on satellite estimates of hurricane wind distribution, Misra says.

However, there are several challenges that could make it difficult to obtain accurate data, Misra says. There is often heavy cloud around the hurricane, which means there is “some uncertainty,” he says.

Another “major practical problem” is that, due to the locations of the satellites, these estimates are only available for the eastern Pacific basin and the Atlantic Ocean, but not for the Indian Ocean or the western Pacific, he adds.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNew technologies such as sail drones, wind-powered vehicles that look like small sailboats and Measure the intensity of hurricaneshelp improve data on hurricanes, Misra says. “But cost becomes an issue,” he says. “How many sailplanes can you really launch to capture the distribution of winds around a hurricane that can stretch for thousands of miles?”

Kerry Emanuel, professor emeritus of atmospheric sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), believes the entire methodology needs to be completely rethought.

“I’m in favor of abandoning the Saffir-Simpson scale and starting over,” says Emanuel. “It’s not a very good measure of the actual risk. The focus so far has been on meteorology rather than risk, and we need to change course.”

However, the Tike metric could face similar problems to the Saffir-Simpson metric, says Emanuel. “Any scale that only deals with wind will fail in many cases, and that’s why we need to replace it,” he says.

“No scale can represent all of these impacts for every location,” Jamie Rhome, deputy director of NOAA’s National Hurricane Center (NHC), told the BBC. To make people aware of the risks of storm surge during hurricanes, the NHC has set up a storm surge monitoring and warning system, he says.

Because hurricanes are “multi-hazard phenomena,” “the National Hurricane Center prefers to communicate the potential impacts of these hazards separately, as they can occur at different times and in different places,” Rhome says.

Traffic light

Emanuel would like to see a new classification system that is “very similar to the one used by the UK Met Office, which simply rates the level of risk on a colour scale and issues a yellow, amber or red warning,” Emanuel says.

“We need to move toward a people-centered rather than a storm-centered framework for hurricane warnings,” Emanuel says.

A more personalized approach that tells people the likelihood of different severe weather events in their area would help them understand their risk level and take necessary precautions, he says.

“We need a separate smartphone app that is risk-based and knows where you are so it can tell you what the chances are that there will be damaging winds in your community or that the water level will flood your house,” he says. “We already do that for regular weather forecasts.”

Emanuel notes that there is a feeling among scientists that “the public is not experienced or intelligent enough to interpret this,” he says, adding that he does not share that view.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, the simplicity of the Saffir-Simpson scale makes it easy for the public to understand. “These categories make it easy to communicate the threat of tropical cyclones, and that’s probably the main reason for the reluctance to replace this metric with something else,” Misra says.

Wehner says it is important for the public to understand that “the Saffir-Simpson scale is not the whole story.”

“I think the public benefits from more detailed information. The National Hurricane Center provides it and good broadcast meteorologists use it effectively,” he says.

Category six hurricanes?

According to a 2020 study, storms are 25% more likely to reach 180 km/h today than they were 40 years ago. Threshold for a major hurricane (Category three and higher).

For stronger hurricanes with higher wind speeds, would it be helpful to add a category six to the existing Saffir-Simpson scale?

But simply adding a category six to describe stronger storms could do more harm than good, Kossin says. “In fact, I think that’s a terrible idea for many reasons,” he says. A higher category, for example, could cause people to dismiss category five as not as dangerous, he warns. “That’s just human behavior,” he says. “Some people will look for any excuse not to evacuate.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAccording to Wehner, NOAA’s National Hurricane Center should ultimately decide whether to add a category six to the current scale.

According to the NHC’s Rhome, Category 5 already describes “catastrophic damage” from wind. “So it’s not clear that there would be another category even if the storms got stronger,” he says. Since most hurricane deaths are water-related, not wind-related, “we don’t want to overstate the wind threat by giving too much weight to the category.”

Wehner shares this view. “The dangers posed by a hurricane are more complex than a single number can express,” he says.

However, some scientists think it makes sense to add a category six. Emanuel says that if we stick with the Saffir-Simpson scale, expanding it to category six would send people a “clear message that climate change is affecting hurricanes. The main benefit would be to raise awareness of that fact.”

Others have concerns about the classification. “Anything above category three should be considered threatening,” says Misra. “People should not wait for a category six to act or react.”

Heather Holbach, a research associate in NOAA’s Hurricane Research Division, also worries that increasing the number of categories could affect how seriously people take lower-rated storms. She sees no scientific justification for a Category six.

“One of my concerns would be: Is this going to make someone think even less of category one or category two, which still pose significant threats?” she says. “I think there’s a big social science component that needs to be much better understood.”

For more BBC science, technology and health stories, visit on facebook. And X.